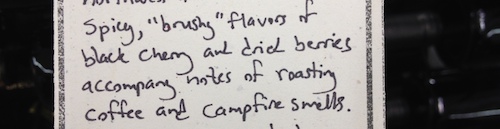

I confess, I like a glass of wine with dinner, and I’m a bottom shelf red kind of gal. It’s better for your budget and it gives you a chance to get some exercise as you peruse the aisles, practicing your squats in order to read the little cards with wine descriptions on them, like this one:

The description is certainly evocative. Already, I can imagine the brush pile I’ve gathered to add to the fire beneath my skillet. In my mind, I see the texture of the sticks, and I can imagine their smell (along with a general sense of being damp and cold, alas). But I still have no idea of how this wine will taste. After all, I haven’t invested any time in developing my palate and taste memory, or a consistent language for talking about these things. I am reduced to relying on descriptions given to me by the wine merchant, and the vague recollection of having enjoyed wines in the past whose descriptions invoked the fabled black cherry (a fruit I’ve never tasted).

Talking about singing shares some of the same challenges as talking about wine. Your experience as a singer, just like your experience tasting things, is completely subjective. No one else gets to hear or feel what you’re hearing and feeling as you sing. We can certainly take guidance from other singers and from our teachers. But ultimately, we must develop our own memory bank of sense experiences, our own language to describe them.

The downside is that there’s a lot to learn. The upside is that the mind loves novelty. When you learn something new in the body, even in an area that seems outside the realm of vocal technique, your sound will benefit. For the singer, the entire body is the palate for the voice.

For inspiration, I offer up the advice of Victor Hazan, from the chapter on tasting in his 1982 book Italian Wine (page 10):

Using one’s nose is the most elusive exercise in tasting. To harness this impetuous organ we need to learn how to add mindfulness to instinct. One difficulty is that the words that describe scents usually reach us with more force than the scents themselves. Such words as rose, violet, pepper, coffee rush to our brain, arousing imperious sensations that do not seem quite to match the ethereal fragrances in wine that go by the same name.

Another problem is our impoverished store of remembered smells. The fragrances of honestly ripened fruit, of wild berries and mushrooms, of field flowers, of wood have been edited out of everyday experience and replaced by those of plastic film, metal foil, polymers, and acetate.

For many of us it will be necessary to replenish the depleted stores of our olfactory memory, conducting our noses through produce markets, gardens, fields, woods, wherever it can assemble the most varied collection of well-identified impressions. Most of what a wine has to tell is spoken by its odors. Smelling is the most intimate contact we have with wine, when we draw close to, as it were, its very breath.

Go forth and smell the world, oh singer, lest ye be reduced to buying the voice based only on the label.