Most singers have what I think of as a Bermuda Triangle area of the voice, the place where you gaze with trepidation upon the score and think: “Oh no! This ship is going down, and no one will ever know what happened to it.”

For me, this place is a single note, D5 (the D in the trebel staff). Even more particularly, an ascending leap to this note, which is smack dab in the middle of my passaggio.

For those of you not familiar with the word, it comes from classical Italian vocal technique, and refers to areas of the voice where the singer must transition between registers. Singing on either side of the passaggio can feel very different, and transitioning smoothly through the area can feel like trying to open a door while holding a chainsaw, three squirming kittens, and a brimming cup of very hot coffee that you must not spill.

Over the years, I’ve had to come to an understanding with my vocal Bermuda Triangle many times. When I get it right, singing my D feels effortless – I could leap to that note all day long. When I land badly? Well, think of your worst day in Junior High, and imagine having to live through that day again, only without pants. A bad sing can be emotionally devastating for any of us. And the bigger the past devastation, the bigger the anticipatory flinch the next time round.

If you’ve ever been downhill skiing, you are perhaps familiar with this situation: You get off the chair lift and survey the slope below you. It’s a lot scarier than what you had hoped for. Not only is it rather steep, but conditions have conspired to put a glaze of ice on the slope, which is now littered with the detritus of other out-hilled skiers, beckoning to you like sirens as you go flailing by. But since the only way out of the situation is down, you gird your loins, say a little prayer to your knees, and chant to yourself the thing your ski instructor said to you in that lesson you had once: “Face the downhill slope.” And it’s amazing how well this rule can work. But the moment you seek to avoid gravity’s influence; the moment you freak out and turn away, as if to claw you way back up the hill, you’re down.

At one time in my life, the feeling of dread I had from leaping into my passaggio was so similar to that of flinching away from a scary hill (and then wiping out), that I started to use the metaphor of facing the downhill slope in my vocal practice.

It makes a kind of sense. When you flinch, you tense up your muscles, and turn away from the perceived threat. In the case of skiing, the threat would be gravity. For singers, the threat is the audience. In both cases, facing the downhill slope is about changing your attitude towards this perceived threat. Instead of seeing gravity or the audience as the enemy, we seek to have a relationship with it, and that relationship can be exhilarating. Downhill skiing can feel like dancing with gravity. When you’re in a good relationship with your audience, it feels like they’re all in the band with you.

So facing the downhill slope became a metaphor for facing my passaggio fears. But the metaphor also had some movement implications that got me into trouble. I developed an assertive singing posture, standing on the balls of my feet, and leaning forward, as if facing a boxing opponent or, say, plunging down the hill on skis. If I was facing my fears, it was in a fighter’s posture, and you certainly don’t want to be fighting with your audience (even on the days when it seems like they want to fight with you).

Fast forward a few years: Enter the Liver.

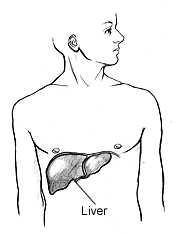

Your liver is principally on the right side of your body, just below the diaphragm, mostly tucked under the lower ribs. It’s a large and dense organ, weighing as much as three and a half pounds. I once had a physical therapist who theorized that people are more likely to tilt their heads to the right than to the left, on account of the relative weightiness of the liver, as opposed to the stomach, pancreas and spleen, over on the left. I have no idea whether this is true or not, but next time you’re in people-watching mode, notice head tilts, and report back. Certainly, you see plenty of singers with an inclination to tilt.

But I digress.

You can help yourself imagine the location of your liver thusly: Put your right hand on the right side of your back, over the lowest ribs. Put your left hand on the front, right side of your body, half on the bottom ribs and half on the belly. Now think of this space between your hands; it is largely occupied by the liver!

Keeping your hands in this position, breathe normally and feel the movement in this area as you inhale and exhale.

Now, as you continue breathing, round your back slightly, and imagine the liver sliding toward the hand on your back. Then arch your back and imagine your liver moving forward into the hand on the front of your body.

Whenever I try a new movement activity, I like to see how it effects the movement challenges particular to singing. So when I first tried liver rocking, I pulled out my personal bête noir of singing-movement challenges, and tried some leaps into the passaggio… and the clouds parted and the stormy seas receded and suddenly the passaggio wasn’t scary at all — it was fun.

I do not mean to suggest that rocking your liver will solve all of your passaggio issues. After all, learning to sing is not about following the recipe; it’s about developing the skills to write your own cookbook.

For me, visualizing the position of the liver and consciously moving it helped release a holding pattern that I hadn’t even realized was there; one that inhibited the movement of my voice. Whereas my “face the downhill slope” metaphor was a complicated version of “don’t flinch”, or “don’t be afraid,” rocking my liver provided a path toward release, towards a feeling of ease.

The big question remains: will rocking my liver help my downhill skiing?