I encourage singers to learn anatomy. (Actually, I think everyone should learn anatomy.) Luckily for us, we live in a time of unprecedented access to information, and it’s relatively easy to find good anatomical illustrations to aid you along the way. There are anatomy apps for smart phones and tablets, videos to watch on the interwebs, and even websites where you can look at 3-D illustrations that can be moved hither and thither with the flick of a mouse. Imaging technology such as real-time MRI has advanced so we can even see films made of the body in vivo.

Before you set out, there are a few things the intrepid singing student of anatomy should bear in mind.

- Anatomical illustrations are interpretations.

- Learning anatomy will not be very useful to you if it’s only theoretical.

- Sometimes you have to reorient the map to make sense of where you’re going.

- There is a downside to studying the dead to understand life.

Singers are familiar with the idea of interpretation, of course. Even though the “bones” of a song remain the same, the performance can vary enormously from one singer to the next.

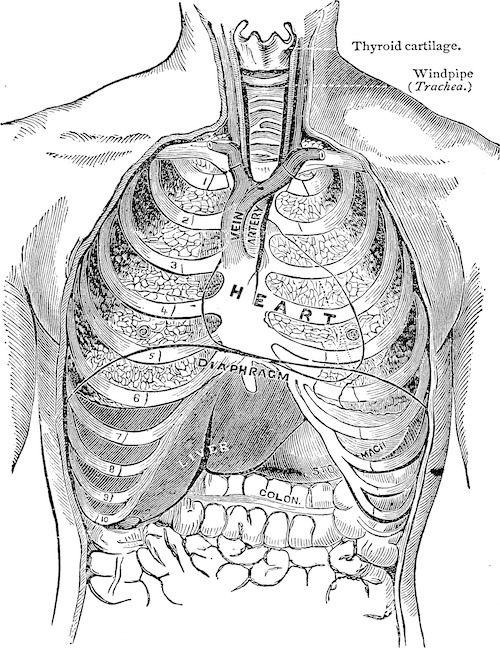

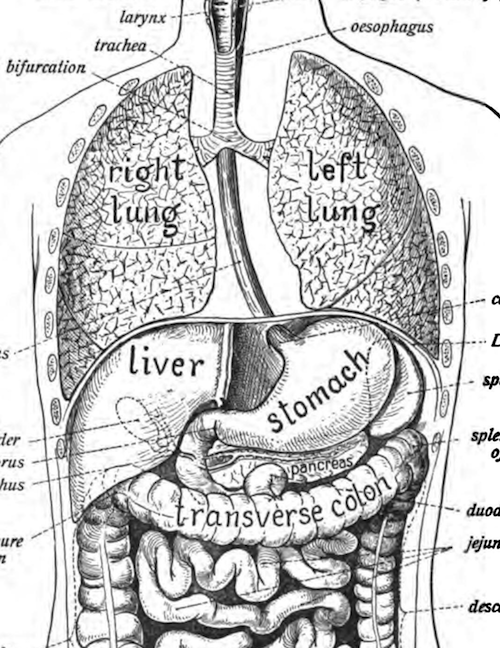

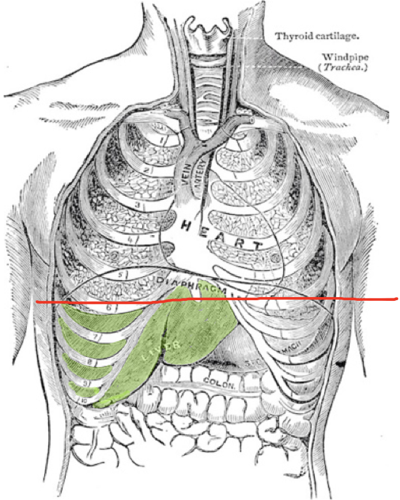

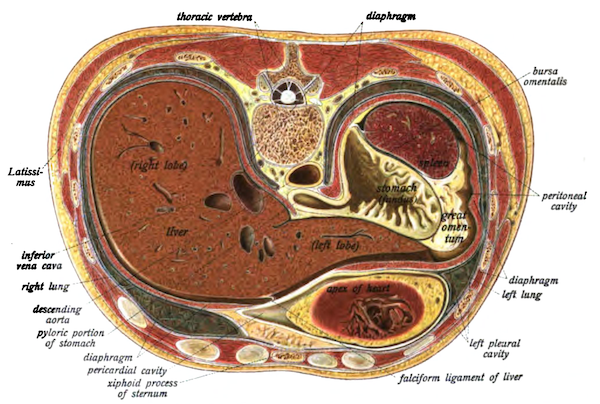

For the artist-anatomist, interpretation involves things like choosing media, figuring out how to show a three-dimensional form in two dimensions, deciding how to “edit the body for clarity” — what structures to include and what to leave out. For instance, here are two pictures of the thorax and upper abdomen showing the organs (click on the image if you want to download the full-size version and do some coloring):

The first illustration is from Frederick Garbit’s 1880 book The woman’s medical companion and guide to health. The second is from Johannes Sobatta’s 1906 Atlas of Human Anatomy. I cropped the latter so both illustrations would show roughly the same area.

Now grab your favorite kid and play the game of: What’s different about these pictures? Here’s one hint: The guy on the right doesn’t have a heart, and part of his liver is missing. But this helps us see what is behind these structures. What else do you notice?

The illustrator isn’t the only interpreter. Bodies are all different. We may have the same basic structure granted by evolution, but that structure is mediated by the genes we’re born with, and also by what we do throughout our lifetime: How we think and move, what we eat, our sleep patterns, how we manage our emotional lives and cope with stress, and what chemicals we introduce into the body, either willfully or involuntarily (those kids in Flint sure didn’t choose to drink lead-tainted water). The artist-anatomist is drawing someone’s body, and those bodies have their own unique stories to tell.

So when you’re setting out to understand some aspect of anatomy, look at as many different illustrations as possible. After all, you wouldn’t claim to understand singing after listening to just one voice!

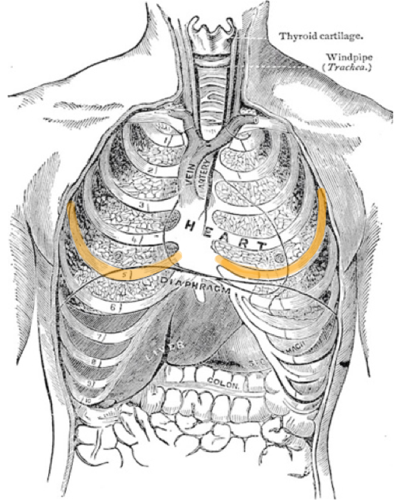

You need to start understanding it in your own body (and yes, this means you’re going to have to touch yourself). For instance, in this drawing, we can see that the dome of the diaphragm is roughly at the level of the fifth ribs, which I’ve highlighted in orange for you:

Have you ever tried counting your ribs and figuring out where that is? Start from the top of your chest, at either side of the sternum. The first rib is hard to feel, as it dives below the collar bones. The first set of ribs you will be able to clearly feel are your second ribs. Count down from there. Remember, always count your own ribs before assisting another passenger. Also, be patient. This is tricky, especially if you have big boobs. In the end, you may realize that the domes of your diaphragm (you have two – one on the right, one on the left) are higher than you thought.

“What’s underneath the diaphragm?” You ask, as you’re working to expand your understanding of breathing. Perhaps you see this illustration and think: “Huh. The liver!”

You decide to follow my suggestion from above and look at some different illustrations. Here’s one from Johannes Sobatta’s 1906 Atlas showing a cross-section of the abdomen. The red line in the above illustration shows the approximate level of the cross-section.

Let’s just say that it’s the same guy as in the illustration above. We’re facing him, and we’ve just cut him in two, and now, still facing him, we’re looking down at the top edge of that slice.

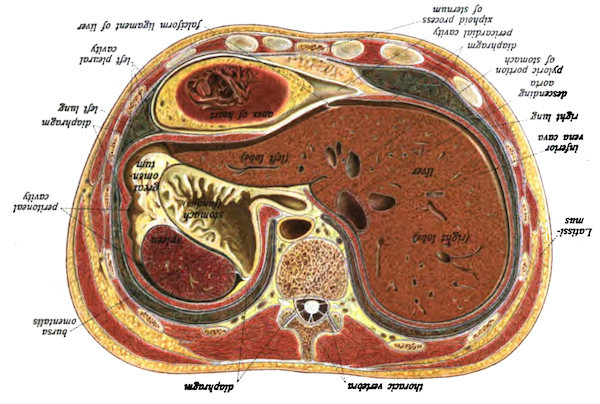

But honestly, we don’t care about this guy’s liver. We’re just trying to figure out our own, and to do so using this image, we’ll flip it around thusly:

Now the legends are all up-side down, but we can look at this cross-section and see that the liver is predominantly on the right (though it clearly crosses the mid line – basically, the liver is huge) and that the stomach and spleen are on the left. We see the vertebra at the back of the body. (It’s worth noting how much in the center of the body the “back” is.)

Orienting the “map” this way makes it easier to use when we’re thinking about our own bodies.

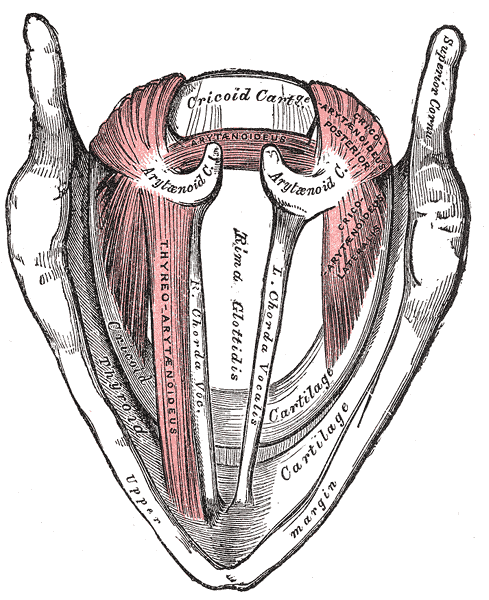

As a singer, I think about the liver a lot. Most don’t. So it’s only fair to offer another map-rotating example from a structure singers are more likely to think about, the larynx.

The following illustration comes from the 1918 edition of Gray’s Anatomy. Because this material is in the public domain, you see it used all over the place, such as in Scott McCoy’s excellent book Your Voice: An Inside View. We can clearly see the vocal cords – chordae vocalis – at the center of the drawing. (These days, you’re more likely to hear them referred to as vocal folds.)

The illustration, like the previously-discussed cross-section of the abdomen, shows the larynx from above, in someone we are facing (as if we’re the clinician about to shove a scope up the nose and down the throat to have a look).

If I want to think about the larynx in my own body, I find it much more useful to look at the image thusly:

The inverted-V shape at the (now) top of the image is the front edge of the thyroid cartilage, which you can distinctly feel in your neck – your Adam’s apple.

The living body moves.

Life and movement are intertwined.

The good news is that if you are reading this, you have a living specimen right to hand — yourself!

We should let the many souls who have come before us — the artist-anatomists and those that contributed the bodies they studied (often without knowledge or consent) — be a source of inspiration for us. They have opened their bodies to us in a way we cannot (while living). Let’s be grateful to their contributions to the world of knowledge, and learn what we can from them.